BRENT HAYES EDWARDS

is a professor of English and comparative literature at Columbia University.

Another Country: the South Bronx Videography and Photography of Martine Barrat

In the early summer of 1978, the Whitney Museum hosted the first major exhibition of the work of Martine Barrat, a French artist who had then been living in New York for about a decade. Titled "You Do the Crime, You Do the Time." the exhibition- part of the museum's New American Filmmakers Series, which had been initiated in 1970 in response to the rapid expansion of experimental art using film and video- gathered videos, photos, and texts drawn from Barrat's extensive work with youth gangs in the South Bronx over the previous seven years. Over the six days of the show (Tuesday, June 6 to Sunday, June 11), there were continuous screenings in the specially. designed Film and Video Gallery on the Whitney's second floor of a pair of videos drawn from the "more than 100 hours" (as the New York Times reported) of half-inch, open reel recordings Barrat had shot in the Bronx, as well as framed black-and-white photographs hung on the walls and laminated color photographs laid out in orderly rows on the floor. The curator Mark Segal later noted that the show drew more than 2,100 visitors, "more than for any previous show of videotapes" at the Whitney, and this "at a time of relatively modest attendance at the museum as a whole."2

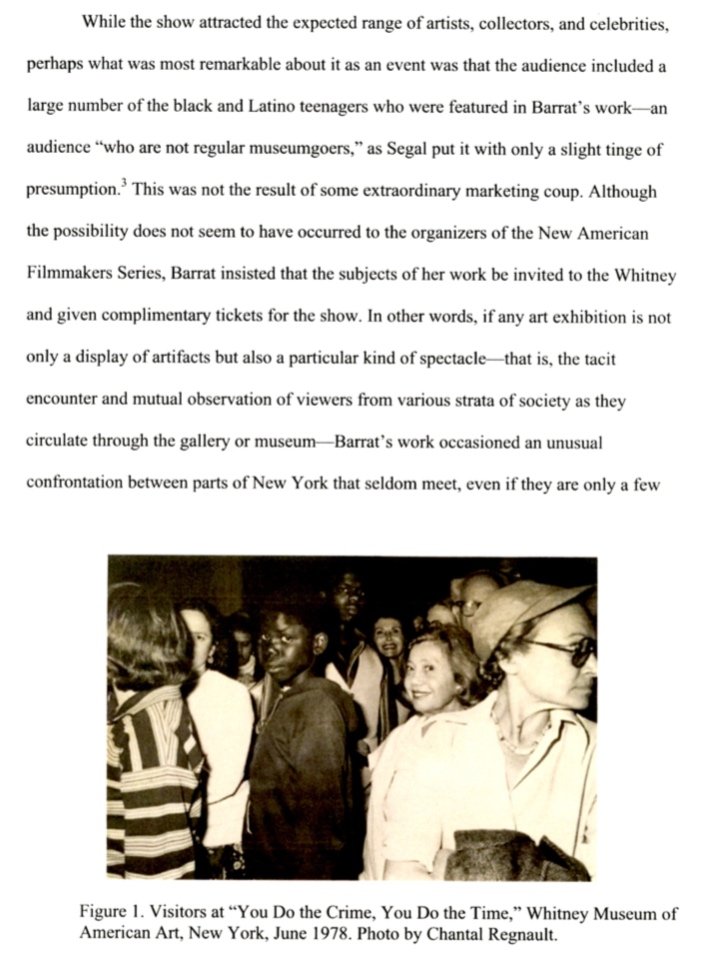

While the show attracted the expected range of artists, collectors, and celebrities perhaps what was most remarkable about it as an event was that the audience included a large number of the black and Latino teenagers who were featured in Barrat's work-an audience "who are not regular museumgoers," as Segal put it with only a slight tinge of presumption.' This was not the result of some extraordinary marketing coup. Although the possibility does not seem to have occurred to the organizers of the New American Filmmakers Series, Barrat insisted that the subjects of her work be invited to the Whitney and given complimentary tickets for the show. In other words, if any art exhibition is not only a display of artifacts but also a particular kind of spectacle--that is, the tacit encounter and mutual observation of viewers from various strata of society as they circulate through the gallery or museum-_-Barrat's work occasioned an unusual confrontation between parts of New York that seldom meet, even if they are only a few miles apart. She recalled later that the teenagers not only took pride in "flying colors" (that is, displaying their gang insignia) in another borough, but also took turns coming to the Whitney every day, speaking to visitors at the show and answering questions "You Do the Crime, You Do the Time" was singular and even radical, in other words, because the show did not simply deliver up images of the South Bronx, that notorious example of 1970s urban devastation and governmental neglect, for the delectation of privileged Manhattan museum-goers. Instead, for half a dozen days, the South Bronx symbolically invaded the Upper East Side, and had the chance to see itself displayed on the walls of power. Or to put it differently, even as her art afforded her entrée into the heart of the establishment, Barrat thought of her primary audience as being the people she portrayed in her work--and this fact explains a great deal both about its unique power and its implicit challenge to the presumptions of the contemporary Western art world. From the perspective of that primary audience, however, the importance of the show had less to do with its symbolic incursion into Manhattan--as thrilling as it was than with a fact that was much simpler, if no less poignant. As Carlos Suarez, one member of the Ghetto Brothers, put it: "We weren't used to seeing ourselves." The Whitney show was widely and warmly reviewed in the press, and most of the articles quoted a biographical statement titled "We Don't Fly No Colors No More" that Barrat wrote around this time with the help of an assistant. In it, Barrat gives a powerful description of what she was attempting to accomplish as a video artist working with youth gangs in the South Bronx: The South Bronx, compared with Harlem, is a community without hope. Life is a matter of survival from day to day. The gangs have developed as a structured response to these conditions. While often violent among themselves, they are also trying in their way to make some positive effort to reverse the deterioration they see around them. In these tapes, I encouraged members of the gangs to use the video camera as a kind of moving pencil to sketch the reality of their lives and relationships with one another and with the outside world. The camera in their hands is often a blunt instrument, but it seems to have a unique power to express the truth of their lives as they see it." Provocatively, she sees her work not as documentary art or cinéma vérité, but first and foremost as a means of expression "in the hands" of the subjects themselves. Rather than a means of producing a reportage about the gangs- or worse, of aestheticizing their “suffering"-for an outside audience, Barrat approaches video as a tool to be shared with the young people she is filming, a way of allowing them to "sketch" and communicate an intelligence, a capacity for self-reflection, that they already possess, as demonstrated by what she calls their "structured" and "positive" response to their living conditions. Barrat had no formal training as a filmmaker. In Paris during the 1960s, she gravitated through a number of artistic fields, but mainly worked as a dancer. In 1966 Ellen Stewart, the founder and director of La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club (the pioneering independent institution in the East Village), saw Barrat dance at the Edinburgh International Festival. Stewart went up to Barrat and announced, "One day, girl, I will send you a ticket to do a show in my theater!"" And somewhat miraculously, two years later Stewart did indeed bring her to the US: Barrat left Paris right after the tumult of May 1968-as she recalls now, Stewart "sent me a ticket just after the revolution!"-to join a delegation to an international theatre festival that Stewart was organizing at Brandeis University.* Barrat then moved to New York and started performing at La MaMa and other downtown venues. After a severe ankle injury ended Barrat's dance career, a fortuitous chain of events led Barrat to the South Bronx and, eventually, to video. She had come to New York with her nine-year old son Stéphane, and soon after their arrival in New York he fell ill with a serious infection. As a foreigner without health insurance, she had great difficulty finding a hospital that would admit him for treatment until she met a Puerto Rican doctor who suggested she take him to Sydenham, a small municipal hospital at 124th Street and Manhattan Avenue that primarily served the African American residents of West Harlem.' While her son was hospitalized, Barrat --who was still on crutches, her ankle in a cast-would often sit while waiting for visiting hours in parks near Sydenham.